How Axe Heads are Made: Traditional and Modern Methods

Modern axe heads are been made by heating a piece of high-carbon steel and either hammer forging or casting or casting it into shape. The blade is then ground, tempered, and sharpened. However, traditionally axes were made by forge welding a hard steel bit onto a head made of softer iron or steel.

Many of these older style axes are still around today – and some blacksmiths will still make custom pieces the old way.

But, no matter how the head is formed the overall process remains the same:

- Shape the head either through forging or casting

- Grind in any final shaping

- Temper the blade to its hardened

- Sharpen, smooth, polish, and finish

How Axe Heads Are Made Today

Around 1900-1920 the cost of good steel was dropping – and the axe industry began making heads entirely from hard high-carbon steel. There are two different methods for forming an axe head from one piece of steel – it can either be forged or cast.

Forged axes are made with steel that is hammered or pressed into shape.

Cast axes are made by melting the steel and pouring them into a mold.

How Forged Steel Axe Heads are Made:

In forging, a single piece of steel is heated to around 1200° C and mailable. The steel is shaped using hammers, dies, and drifts to form the axe head. The steel can be continually reheated and hammered until the shaping is complete.(1)

Open-Die Forging Offers Control and Customization

Open-die forging requires a skilled worker to shape each axe head individually, using (modern) blacksmith tools – and is done by higher-end brands and custom shops.

Individual blacksmiths use a single electronic hammer, swapping out dies or using hand-held dies and drifts to shape the head.

Large axe manufacturers will have giant multi-stage hammers with many specialized dies attached at once to allow quick and consistent shaping. These hammers can strike 80 times per minute, with a force around 180 tonnes(2). The video below shows the process:

There is a longer video (8min) from Gransfors Bruk here that shows more steps in the process as well.

Close-Die Forging Can be Automated

Some manufacturers (like Estwing) use closed-die forging that actually shapes everything in one press, so they can be made much quicker and cheaper.

How Cast Steel Axe Heads are Made:

Casting is a cheaper way to make axe heads that takes less skilled workers to produce consistent results. This is how many of the cheapest axes are made.

An axe head can be cast by fully melting steeling and pouring it into a mold. Once the steel solidifies the head is ground smooth with a belt grinder, tempered then sharpened.

This process is faster and cheaper because it’s easy to operate at scale, and can even be mostly automated.

Forged vs Cast axes:

Forged steel is stronger than cast steel.

Steel has a grain structure – and when an axe head is forged the structure stays intact and is even compacted. When steel is cast the structure of the melted steel becomes randomized which decreases the strength.

There are more factors at play like the quality of the steel, and many cast steel axes are still totally fine axes. But that’s part of why premium axes are all forged.

The other difference is craftsmanship. It takes the time of a skilled worker using an auto hammer to forge an axe head. Where a cast head can be made much quicker or even automated.

Finishing the Axe Head

Once the axe head has its overall shape, it still needs to be cleaned up, tempered and sharpened.

Final Shaping

The steel can come out of the forge with some rough edges and a little thick in the blade. The Hot axe head is quickly scrubbed with a brush to remove any debris from the forging.

Once cool, any remaining blade thinning, or grinding to finish the overall shape is done on large belts before the blade is tempered.

Tempering the Bit

In order to properly harden the steel blade, the steel is reheated to a specific temperature and the blade (bit) is dipped (quenched) in oil. This process is called tempering.

Tempering hardens the steel making it suitable to hold an edge and withstand use as an axe.

Note: Some axes also have a hardened pole (back of the head) for striking splitting wedges or being used as a hammer.

Sharpening and Finishing Touches

Once cooled from tempering, the axe head can be properly sharpened, polished, painted, oiled, hung, labeled, and any other finishing needed to go to market.

How Axe Heads Were Traditionally Made (2-piece):

Before quality steel was easily accessible and cheap enough to use for the whole head, axes were made by shaping a head out of iron or a softer (cheaper) steel, and then a high-carbon bit was forge-welded onto complete the head.

While the forge was always involved – cast elements were sometimes used even in the late 1800s. Many high-quality axes were made using both forged and/or cast parts.

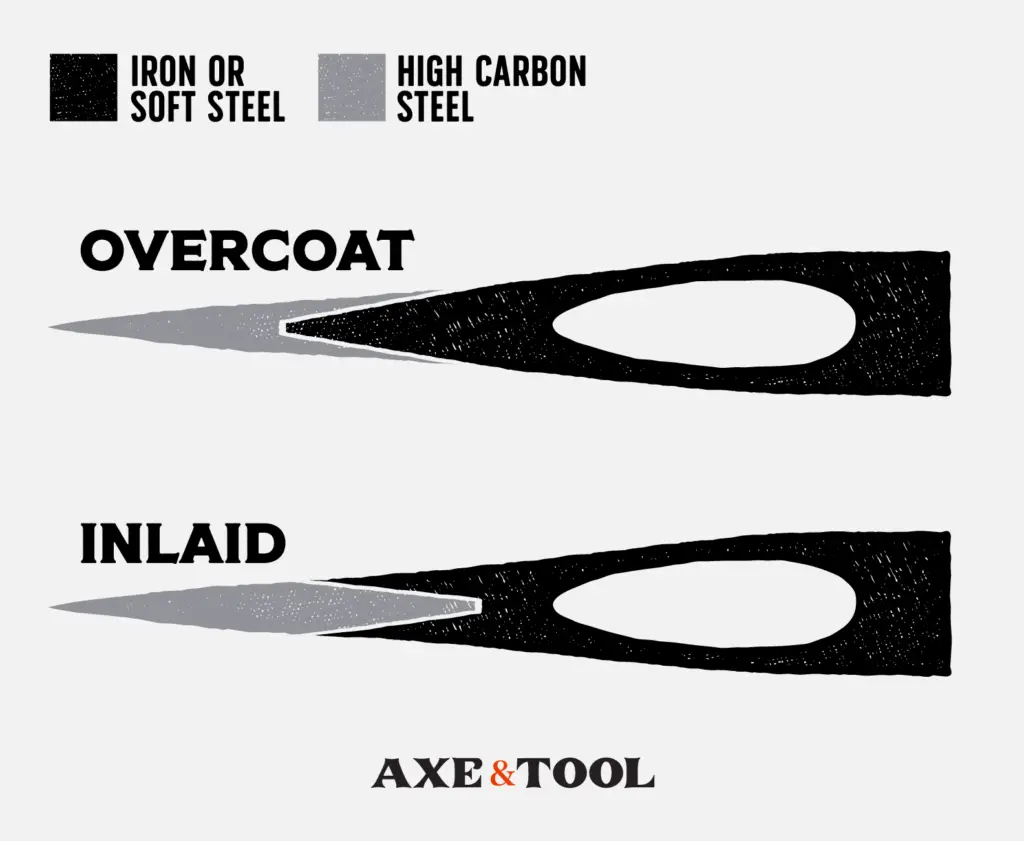

However, the main two variations of axe making at this time, were if the hard steel bit was inlaid or over-coated when attached to the body.

Axes with Inlaid Bits

Some axe makers inserted the hardened steel for the bit in between the two sides of the head made from softer steel or iron. This is an inlaid or inserted bit.

There is a great video (here) [8-min] of an axe being made of iron with an inlaid bit.

Axes with Overcoat Bits

Other axe makers would forge the head, then wrap the hard steel bit around the outside of the cheeks. This was called an “overcoat”.

Some higher-end axes would offer double or trip overcoat steel meaning tempered area would go back further.

Inlaid vs overcoat axe bits.

Like many choices, there were staunch believers who toted the superiority of each method – but in reality, it doesn’t seem to have made a difference. The axes would have the same amount of tempered steel, the same lifespan, and ability.

Some major manufacturers used both methods for different brands, and both were used by high-end axes up until the switch to single steel.

Can you tell how an axe was made?

If you have an old axe you can often tell which method was used from the direction of the weld lines on the top or bottom of the axe blade. Although, axes of this age often have a heavy patina and/or pitting, so it can be hard to tell.

If the patina is removed, It’s easier to tell as the harder steel is darker and often less pitted.

Sources:

About the author:

About the author:

Jim Bell | Site Creator

I’m just a guy who likes axes. I got tired of only finding crap websites, so I set out to build a better one myself.

I’m also on Instagram: @axeandtool

Please comment below If I missed something or if you have any questions. I do my best to respond to everyone.

Great article, Jim! Lots of solid content per usual. If desired, you could expound the heat treat info to include: heating to a specified temp, quenching (which hardens the steel), then tempering (which softens the hardened/brittle steel some, making it tougher and less prone to breakage). Many makers use ovens for tempering that never get above the intended temper temp.

Others (and traditionally) the bits were ground after hardening to reveal fresh steel, then the head was heated in the forge (often poll first) until the heat drew into the bit (to “draw out the temper”) as evidenced by a change in color (often straw colored) in the freshly ground steel in the bit. At this point it was quenched again to fix the temper.

Great points – I think I will have to take another pass to fill the gaps. I’ve seen old ads that highlight “ground before tempering” but I didn’t know the details of the second temper for the bits ground after. Appreciate the insights!