The Anatomy of an Axe

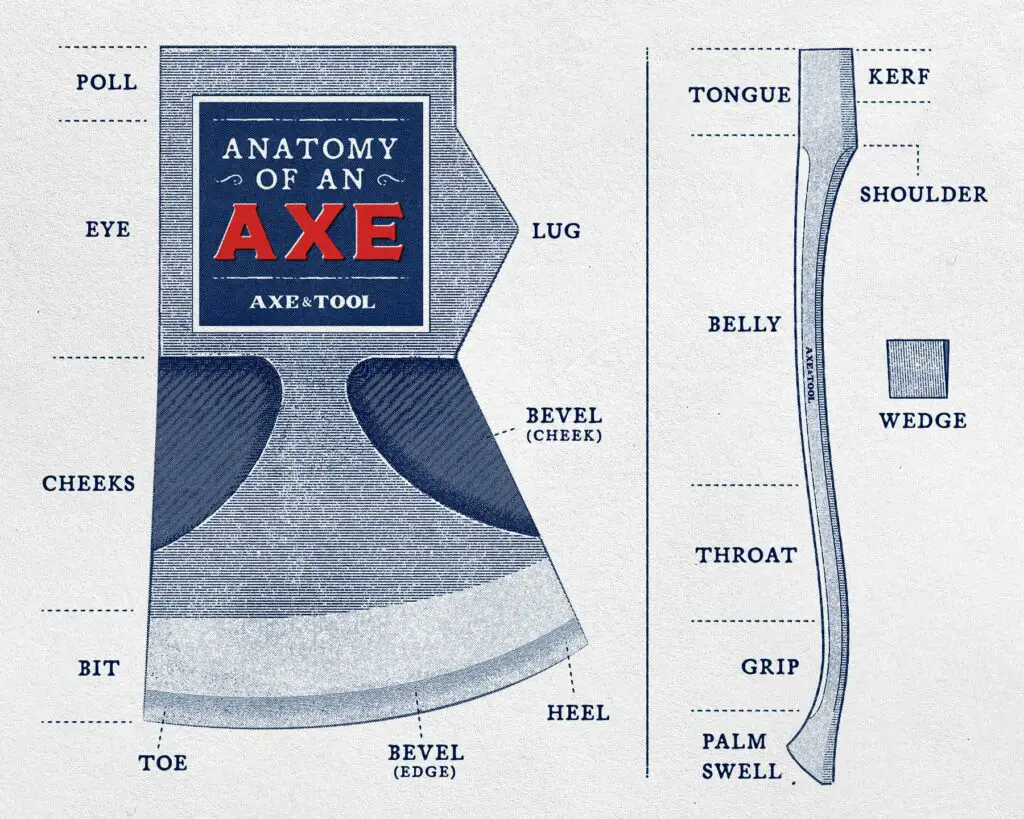

An axe is made from three main parts; a head, a handle, and the wedge that holds them together. But the anatomy of an axe goes deeper than that. Both the head and the handle have unique features with distinct names, like the; toe, heel, cheeks, poll, eye, tongue, shoulder, belly, beard, throat, and more.

The word “anatomy” makes sense because of the number of body-based words used to describe an axe. And, in some cases it makes sense – the head sits on the shoulder. But, you also end up with a tongue in the eye and a toe on the head.

I’ve broken down the anatomy by major parts, listing descriptions, and alternate names, and added diagrams to make it easy. There is a quick TLDR table below, but keep reading for more in-depth illustrations and writeups further down.

Anatomy of an Axe Head

The head of an axe is a sharpened wedge-shaped piece of steel that is hung on a handle to be used for chopping, cutting, or splitting wood. At its core, the head IS the axe. Axe handles can break and be replaced, but a new axe head is a new axe. The designs can vary depending on the intended use.

The differences in designs and possible benefits are easier to identify once you understand the parts that make up an axe’s head and know where to look. I’ll start at the pointy end and work backward.

If you want to see just how many different types of axes there are, check out the illustrated encyclopedia of axe types.

The Bit

The bit is the first 1-2 inches of the blade where the steel has been tempered and hardened to hold a strong cutting edge. The term is from the historic axe-making technique, where a separate “bit” of high-carbon steel was forge-welded to the rest of an iron or softer steel axe head.

Today axes are made from a single steel, but still, only the first inch or two is tempered and hardened – forming the bit.

Technically, the bit doesn’t have to be a blade. Axes like fire axes with a spike on the back would be considered to have two bits because the spike would also be a hardened edge.

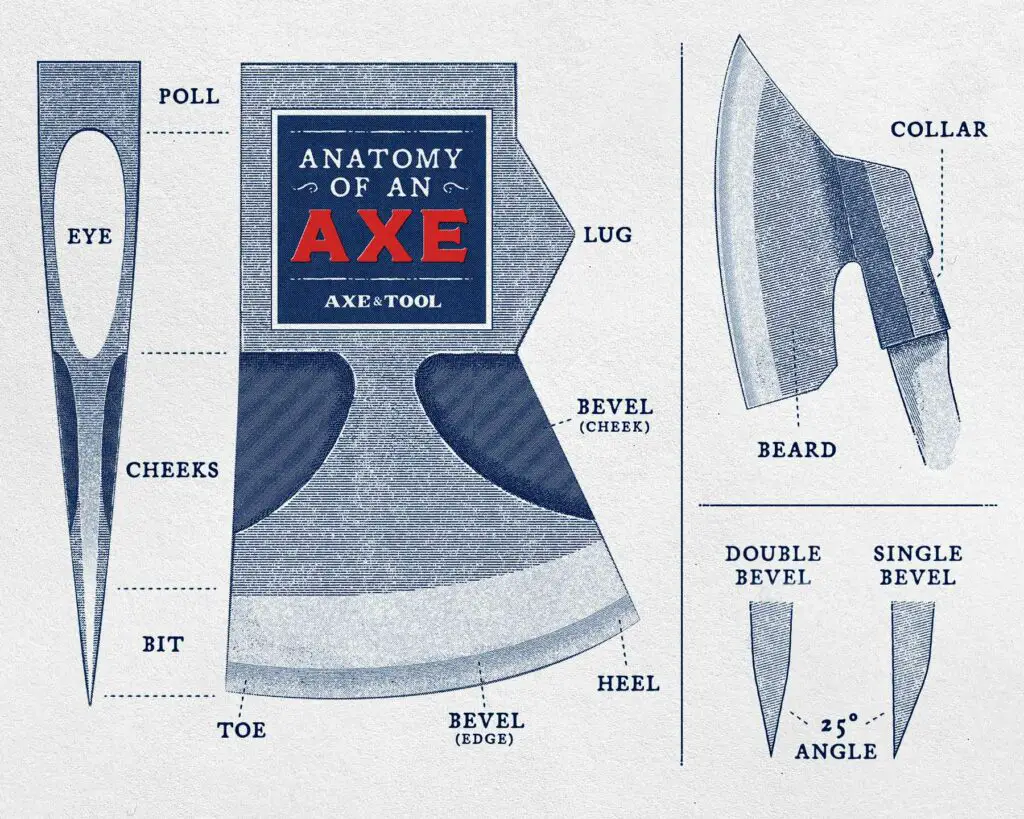

The Bevel

The bevel of an axe is the final taper at the edge of the bit where the blade is ground down and sharpened to create the cutting edge. The bevel is typically symmetrical and tapered to around 30° for chopping or splitting axes. However, axes with one-sided are used for specific hewing or carving tasks.

The shape and angle of the bevel can vary depending on the intended use of the axe and the user’s preference. A more aggressive bevel angle under 25° can provide better cutting performance, while a wider angle may offer more durability.

Traditionally the bevel transition from the rest of the head is rounded, but You can also find flat ground bevels for more precise carving tasks.

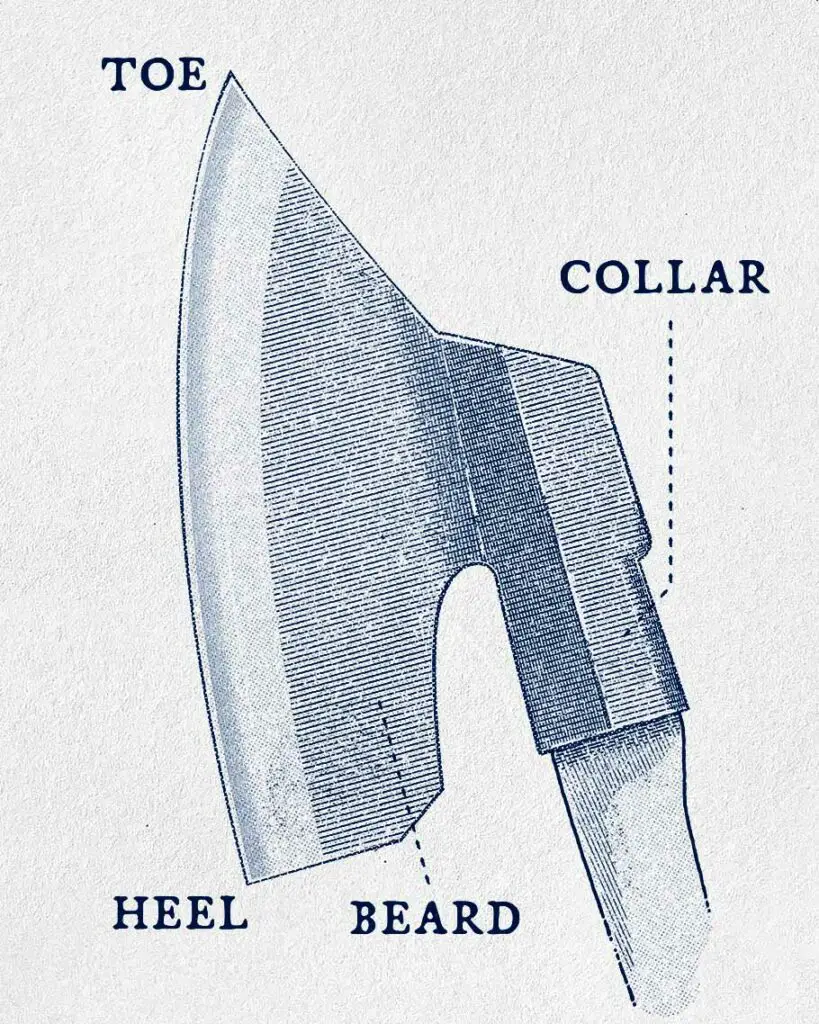

The Toe

The toe of an axe is the top corner blade or bit.

When you find old axes, the toe is almost always the most worn-out part of the bit. That’s because of years of use the top corner ends up the dirt the most often, getting chipped on rocks and needing to be filed back.

The Heel

The heel of an axe is the bottom corner of the blade or bit.

The Beard

While the heel of most axes flares down, most axes do not have beards.

The beard of an axe is part of the blade that drops unsupported below where it connects to the head. The back of the beard runs nearly parallel with the handle, creating a gap behind the blade that allows users to use various grips, and to hold for precise cutting tasks.

Note: There is some variation in how the term beard is used. Some folks use it to describe the shape or angle of the transition from the heel to the eye area. However, I stand by the explanation above – come fight me internet.

The Cheeks

The “cheeks” are the sides of an axe head between the eye and the cutting edge. They can vary in shape and thickness depending on the intended use. They can be flat, or curved, have spines, grooves, flared ramps, or cut-out bevels.

The Eye

The “eye” of an axe is the hole in an axe head where the handle is inserted. The shape and size of the eye can vary depending on the design and purpose of the axe.

Cheek Bevels

Some axes have indents or bevels cut into the cheeks. These bevels reduce friction when chopping allowing the axe to cut deeper and be easier to remove.

There have been many different bevel designs over the years, a prominent one being “phantom bevels”. Historically that was a specific design of bevel, but I think it is too cool a name to ignore, so many people misuse it as a more general term.

The Poll

The “poll” of an axe is a portion of steel that extends off the back of the axe head to act as a counterweight for the blade to make the axe easier to swing precisely. It became a prominent design feature and innovation in North America, where large axes were needed to fell large trees.

Depending on the design of the axe the poll can also perform additional tasks like banging on felling wedges, and some axes even have a hardened poll that can be fully used as a hammer. but, most are not and cannot be used as a hammer without damage.

Not all axes have a poll, many designs outside of North America simply stop at the eye.

Lugs

Some axe heads have metal lugs (ears) that drop down on either side of the eye to increase the grip on the handle and reduce the chance of loosening. Lugs can be pointed or rounded, and have been used on countless types and models of axes for centuries.

The common patterns seen with lugs are Jersey and Kentucky pattern chopping/felling axes. Also, the popular Swedish forest axes (Gransfors Bruk & Hults Bruk).

Collar

Collared axes have a steel tube dropping down from the bottom of the head, extending the eye. This creates more hold with the handle (similar to lugs) and can protect the handle from damage. The design was popular in Scandinavia and parts of Europe, but can be found in North American designs as well.

Anatomy of an Axe Handle

The axe handle was traditionally called a haft or helve. But, while all three names still apply – I think axe handle has won out as the most commonly used term.

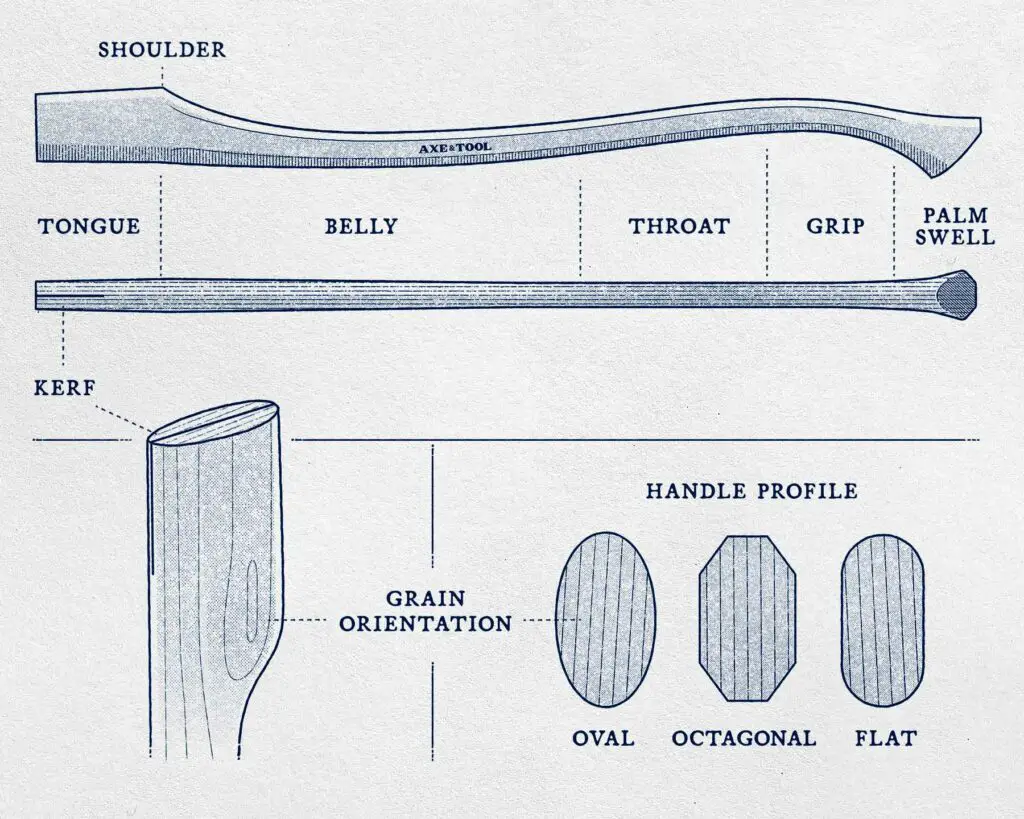

The Tongue

The tongue is the shaped end of the handle that gets inserted into the eye of the axe head. A teardrop shape is most common, but different regions and styles of axes can have different shaped tongues.

The Kerf

A kerf in an axe handle is the cut in the tongue where the wood wedge will be inserted to lock the head to the handle. The kerf should be cut about ⅔ the depth of the axe head.

The Shoulder

The shoulder of an axe handle is the area right below the tongue that gently flares out to prevent the axe head from sliding down the handle. Modern axes often have a shoulder that is way too wide. It should be wider than the eye, but not wider than the axe head.

The Belly

The “belly” of an axe handle starts below the shoulder and runs about halfway down the remaining handle with a gentle forward curve.

The Throat

The “throat” of an axe handle starts below the belly with a curve backward and is the transition into the grip. The throat width often thins slightly compared to the belly and grip.

The Grip

The “grip” is the bottom of the handle, held in the axe user’s off-hand and used to control the axe.

The Palm Swell

The palm swell acts as a hand stop at the bottom of the handle to keep the handle from slipping from a user’s hands.

What Holds an Axe Together

The final pieces in the anatomy of an axe are what keep it all together.

Wedge

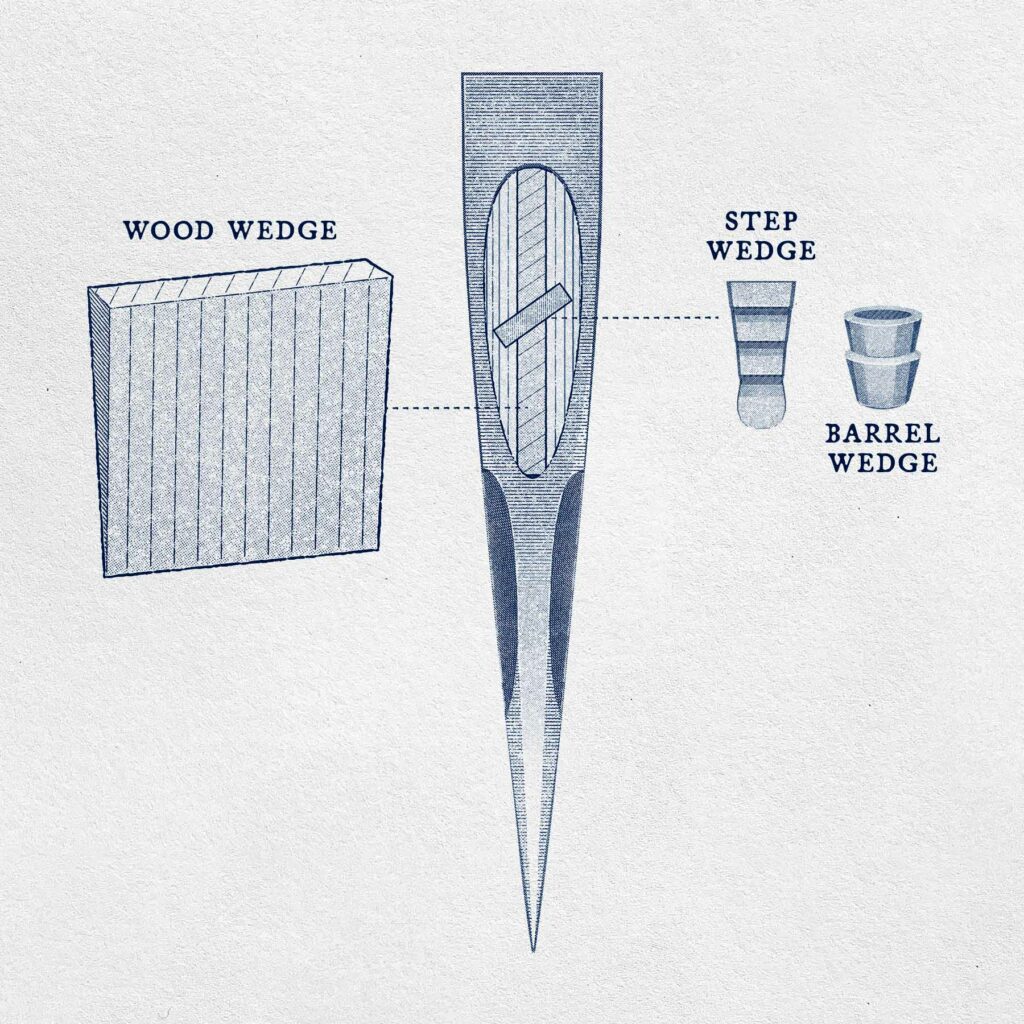

A wood wedge is hammered into the kerf once the head is on the handle. The wedge presses the handle into the inside of the eye, holding it in place. These are usually made from a softwood like poplar, to compress and fit the eye snuggly.

Check out my complete guide to axe wedges if you want to learn more about other wood types, wedge sizes, and angles for wedges.

Cross-wedge

Sometimes a metal cross-wedge can be hammered in across the wood wedge to add additional pressure and keep the axe head firm.

Traditionally these metal wedges were only added once an axe started to loosen, and if the axe is hung properly it shouldn’t be needed. However, starting in the 1970s most manufacturers now install them as extra protection against a less-than-ideal hang during mass production and less stringent quality control.

Barrel-wedge

Some axe makers use a circular step wedge as an alternative to a cross-wedge that adds even more pressure within the eye of the axe.

Please comment below If I missed something or if you have any questions. I do my best to respond to everyone.

About the author:

About the author:

Jim Bell | Site Creator

I’m just a guy who likes axes. I got tired of only finding crap websites, so I set out to build a better one myself.

I’m also on Instagram: @axeandtool

Sources

- USFS Axe Manual – One Moving Part

- Yesteryearstools – Glossary of terms

- Dirtydirtywrench – Consulted for article